History of the Spanish Plate Fleets

The Spanish Plate Fleets lost off of the coast of Florida have long evoked awe and fascination. Named the “Plate Fleets” for the plata (silver) coins they carried, the remains of these fleets weave an archaeological tale of international trade, colonialism, piracy, high seas adventure, and tragedy. Beyond the gold and silver that was scattered on the sea floor, the wrecks of the Plate Fleets provide insight into the economy of the Spanish empire and maritime culture of the 18th century.

The vast amount of natural resources discovered in the New World funded Spain’s rise as a world power. Spanish shipments of silver, gold, gems, spices, and other exotic goods soon became prey for pirates. To counter this threat and to protect its merchant vessels from predators, Spain developed a formal convoy system as early as 1537. At least two armed escorts, a flagship (capitana) sailing at the front of the fleet and a vice-flagship (almiranta) in the rear, accompanied the heavily-laden ships across the Atlantic. Additional armed galleons often protected larger fleets.

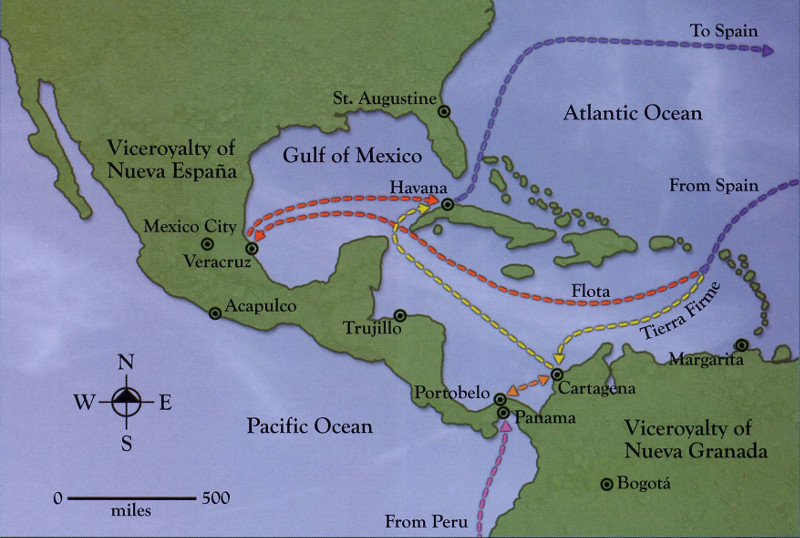

Each year, two separate fleets left Spain loaded with European goods that were in great demand in the Spanish-American colonies. Sailing together down the coast of Africa, the fleets stopped at the Canary Islands for provisions before the long voyage across the Atlantic. Once they reached the Caribbean, the two fleets separated. The New Spain fleet, or flota, sailed to Veracruz in Mexico to take on silver and other goods, such as porcelain shipped from China and brought overland from Acapulco, Mexico, by mule train. The Tierra Firme fleet, or galeones, traveled to Cartagena, Columbia, to take on South American products. Some ships were sent to Portobelo in Panama to pick up Peruvian silver, while others went to the island of Margarita to collect pearls harvested from offshore oyster beds. Other New World products included indigo and cochineal dyes, exotic woods, ceramics, leather goods, chocolate, vanilla, sassafras, tobacco, and products made by the native peoples of the Americas. Once loading was completed, both fleets sailed for Havana, Cuba to rendezvous for the journey back to Spain.

The fleet faced many dangers as it made its way back to Spain. The ships traveled through poorly-mapped reefs that could easily sink them. The slow moving, heavily-laden galleons were also prime targets for pirates during the “golden age of piracy.” One of the greatest fears was tropical storms and hurricanes. With no way to forecast the storms or to predict their tracks, ships were completely at the mercy of wind and waves.

Under the fleet system, which lasted until nearly 1800, Spain successfully transported enormous amounts of goods between Europe and the New World. Some ships inevitably wrecked along the way, and the Spanish developed effective salvage capabilities to recover the valuable cargoes. Major fleet disasters occurred in 1622, 1715, and 1733. The remains of these ships now provide us with exceptional opportunities to study this part of our maritime history. Starting in the 20th century, people began recovering artifacts from these ships off of the coast of Florida using diving gear and drag lines. Many items of historical significance found in State waters are curated by the Florida Bureau of Archaeological Research and made available to researchers and museums to further our knowledge of this pivotal time in the history of the Americas.

The 1715 Plate Fleet

The 1715 fleet was overladen with goods from the New World. Because of shipping disruptions due to the War of the Spanish Succession (1701–1714), which had recently ended, the fleet was carrying a total of four annual shipments back to Spain. Loaded with the products of South America, Mexico and the Philippines, a Spanish convoy commanded by Capitán General Don Juan de Ubilla rendezvoused in the summer of 1715 with the South American squadron of Antonio de Echeverz at Havana, Cuba, to begin the long voyage back to Spain. The combined fleet of twelve vessels set sail from Cuba on the 24th of July.

Only a few days out, the fleet was struck by a fierce hurricane off the coast of Florida. Eleven of the twelve ships in the convoy wrecked, killing over 1,000 people. The ships were scattered along approximately 50 miles of the Florida coast from Sebastian Inlet to Ft. Pierce Inlet. Survivors of the wrecks subsisted on food from the stores of Miguel de Lima’s cargo ship, Urca de Lima, which was grounded by the storm but left relatively intact. Supplies finally arrived from Havana, thirty-one days later. Although many precious goods were recovered from the wreck sites shortly after the disaster, salvage attempts soon ended as sand engulfed what was left of the ships and their cargoes.

The 1733 Plate Fleet

Tragedy struck the Spanish Plate Fleet again in 1733. The flota, commanded by Lieutenant-General Rodrigo de Torres aboard the sixty-gun navío, El Rubi, consisted of three other armed navíos, sixteen merchant naos, and two smaller ships carrying supplies to the Presidio of St. Augustine. On July 14, 1733, a day after departing Havana, Cuba, the crews sighted the Florida Keys as the weather worsened. Sensing an approaching hurricane, Lieutenant-General Torres ordered his captains to turn back to Havana; his orders came too late. By nightfall of July 15th, most of the ships had scattered, sunk, or been swamped along 80 miles of the Florida Keys. Only four ships made it safely back to Havana. Another vessel, the galleon, El Africa, managed to sail on to Spain undamaged.

Survivors of the wrecks gathered in small groups throughout the low islands and built crude shelters from debris that washed ashore. Spanish admiralty officials in Havana, Cuba, who were worried about the fate of the fleet, sent a small sloop to search for wrecks. Before the sloop could return, another boat arrived in Havana harbor and reported seeing many large ships grounded near a place called “Head of the Martyrs.” Immediately, nine rescue vessels loaded with supplies, food, divers, and salvage equipment sailed for the scene of the disaster. Soldiers were on board to protect the shore camps and the recovered cargo. Operations at the wreck sites continued for years as the salvors worked under the watchful scrutiny of the guard ships. When a final calculation of salvaged materials was made, more gold and silver was recovered than had been listed on the original manifests. Many individuals had smuggled unreported goods aboard, a common practice to avoid paying taxes to the crown.